PFAS, THE EUROPEAN MAP OF ETERNAL POLLUTANTS

Read our series on the case of Spinetta Marengo chemical center, one of the hot spots of contamination of PFAS in Italy.

For decades, per-polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have allowed us to obtain materials with unique properties. We use PFAS everywhere, from clothing to food wrappers, from non-stick pans to cosmetics. However, it has been known for years that PFAS persists in the environment forever and can have serious health consequences. Contamination often begins from the places where these substances are produced and used, as is the case in Piedmont, at the Solvay plant in Spinetta Marengo, a small town just outside of Alessandria.

In the air, water and soils near the chemical plant, PFAS are not the only substances that lead to a situation of serious environmental pollution. In fact, PFAS are accompanied by toxic compounds such as chloroform or hexavalent chromium, legacies of multifaceted historical contamination. Pollution results in health effects for those living in these areas. The few investigations conducted so far have yielded disturbing results.

Institutions are struggling to provide answers due to a chronic lack of tools and resources. The company is intertwined with the dynamics of the territory. The population lives with this massive chemical center and observes it with detachment. In Spinetta Marengo, a few people fight tenaciously to claim the right to health of the entire citizenry.

From chromium to PFAS, History of a centuries-old pollution

Alessandria lies at the center of the Torino-Milano-Genova industrial triangle. The city lies on a wide alluvial plain, embraced by two rivers, the Bormida and the Tanaro. The former flows into the latter and then flows into the Po. Spinetta Marengo is a fraction of Alessandria, one of the suburbs of Fraschetta, a vast area to the east of the city. The lowland landscapes – infinite horizons shrouded in fog during the cold months – were the scene of the Battle of Marengo, fought on June 14, 1800, between Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops and the Austrian Army.

The road from Alessandria to Spinetta Marengo is the only link between the city and the area to the east called Fraschetta, which is heavily affected by PFAS and the past pollution. Alessandria, Italy, January 19, 2023.

The statue of Napoleon in the garden of the Marengo Museum looks at the Solvay plant, which is less than a kilometer away as the crow flies. Alessandria, Italy, January 13, 2023.

Spinetta Marengo is home to a major chemical center, founded in 1905, which has since then guided the fortunes of the village, its inhabitants and the entire area. The chemical center, at first dedicated to the production of copper sulfate, has changed hands several times during its century-long history. In 1933 Montecatini became the owner of the company, the railroad link that still serves the plant today was built. In 1966 Montecatini merged with Edison, becoming Montedison. In 1992 the company took on the name Ausimont.

Over the decades, everything was produced in Spinetta Marengo. For a long time the plant dealt with the chemistry of strong acids, such as sulfuric acid or hydrofluoric acid. Until the early 1970s, chromates and dichromates were produced in what have been called the “departments of death.” Workers who were part of the “tribe of pierced noses,” a stigmatizing expression referring to a particular harm caused by occupational exposure to certain substances, worked there. The acids consumed tissue, nicked cartilage, and hollowed out cavities joining nose and throat. Later the business changed and turned to chlorine and fluorine chemistry. Fluorinated elastomers began to be produced, for which there was a need to use PFAS. The factory, despite everything, was generating wealth.

a safe place

In Spinetta Marengo lives Paola [name is fictional]. Her husband – for a lifetime worker at CeRPi, the chemical center’s Pigment Research Center when it was owned by Montedison – died of cancer. «He knew I was allergic to peach peels. For 50 years he peeled them for me so that I could eat them without having itchy hands. That was him. He never talked about the factory. I think back to his overalls, which the more I flapped them, a very fine dust kept coming out. But the factory was a safe place and it gave food, he said.»

Paola, sitting in the kitchen, is surrounded by photos of her husband and recalls that «doctors told me that the disease could not be hereditary. So many of his colleagues also got sick and died. With their families we became civil parties in the trial that took place many years later. I wanted to understand the cause of the disease. I was accused of doing it for the money. But I didn’t care. They could have given me all the money in the world, they would never give him back to me. My relatives say I should fix the house, but I don’t want to. The house should remain as it was when he was still there, with his clothes in the closet and his shirts in the drawer.»

The plant has belonged to the Belgian multinational Solvay since 2002 and produces fluorinated polymers. In this context, PFAS are needed to make the substances that are then sold to many manufacturing companies, which use them to make countless products. PFAS such as ADV 7800 and PFOA are or have been used in Spinetta Marengo, the latter being classified as a suspected carcinogen and replaced by cC6O4, a molecule for which Solvay holds the patent. PFAS are thus added to the long list of pollutants that have contaminated the land.

water, sugar and poison

Spinetta Marengo’s widespread environmental problem continued to go unaddressed. Many – too many – families told of their relatives who had passed away because of cancer. The fumes from the factory’s 72 smokestacks were the subject of jokes in village bars. People were careful not to use well water. In the past, plant leaves would turn yellow and fall to the ground for no reason, but more recently the pollution phenomena have become less and less noticeable. The population began to feel calmer. But the contamination continued and was enriched with new substances, including PFAS. Over the years very few people had tried, unsuccessfully, to draw attention to a serious and known problem. Everyone knew. No one was acting.

The Solvay plant in Spinetta Marengo seen from an abandoned field along via Genova, the town’s main street. People say that when the weather is cold, fumes from the Solvay plant condense and fall like snowflakes settling with frost. Alessandria, Italy, Dec. 13, 2022.

Finally, between 2007 and 2008 the pollution was officially recognized thanks to a completely coincidental event. There had been a request from a well-known supermarket chain to buy the land where a sugar factory stood – not far from the factory and decommissioned for many years – to build new commercial buildings. To get the necessary permits, groundwater analysis was conducted.

The results obtained made the authorities and the population pale: in the surface water table and soils lay the legacy of decades of environmental neglect. A process began to determine who was responsible for the historical and ongoing pollution. The trial concluded in 2019 with the conviction of executives from both Ausimont and Solvay.

The results obtained made authorities and the public pale: in the surface water table and soils lays the legacy of decades of environmental neglect.

In the past 15 years, since the scandal broke out, something seems to have changed. A section of the population has begun to make legitimate claims for environmental justice. Awareness of situations now deemed unacceptable has changed. Some people decided to take action: this is how the STOP Solvay committee was born.

The buildings of a sugar factory in Spinetta Marengo, abandoned 30 years ago, are overgrown with wild vegetation. The sugar factory site borders the city’s main road on one side and the Solvay plant on the other side. The sugar factory site is heavily polluted with asbestos and other chemicals and has never been cleaned up. Alessandria, Italy, December 14, 2022.

A few raindrops on fallen leaves inside one of the buildings of the abandoned Spinetta Marengo sugar factory. The drops are potentially polluted by PFAS emitted from the neighboring Solvay plant. The sugar factory site borders the city’s main street on one side and the Solvay plant on the other side. Alessandria, Italy, December 14, 2022.

A three-stage epidemiological investigation

«My family is from Spinetta Marengo. In my life I worked moving around a lot. When I came back here I started to get informed and involved, because it was clear what was going on», says Claudio Lombardi, a retired Automotive engineer and former environmental counselor in Alessandria. Lombardi is part of the STOP Solvay committee and is one of the key figures animating the debate. «Since 2012, as an alderman, I wanted to get to the bottom of problems that we knew about but had not yet demonstrated. It was important to be able to go into the administration to have documentation. An epidemiological investigation had to be done, coordinated in three phases», he explains.

«The first phase looked at the Fraschetta population of about 20,000 people. The second phase compared the population of Spinetta Marengo with that of Alessandria, its Province and the region. The Third phase, which we have been asking to start for years, should lead to a screening of the population to establish the presence of a link between pollutants and diseases.»

Engineer Claudio Lombardi, 80, at his home in Spinetta Marengo on March 4, 2023. Lombardi was elected Councillor for the Environment of the City of Alessandria in 2012. During his tenure, he carried out the first epidemiological survey revealing the higher incidence of several types of cancer in the population of Spinetta Marengo compared to a control study.

The results are the first two phases of the investigation – Although disputed by Solvay – In Spinetta Marengo, people are getting sicker. In both surveys, the statistically significant results cover many diseases, such as various types of cancer, neurological diseases, endocrine and metabolic diseases. This path to know the real impact of the chemical plant’s pollution on people’s health stopped during the term of the penultimate city council, between 2017 and 2022. A matter of different sensitivities, they say. The fact remains that where institutions fail to provide answers, it is the citizenry itself that takes the initiative.

PFAS, health and the absence of a health protocol

The STOP Solvay committee worked with a group of journalists from Belgian national television to carry out a survey on the amount of PFAS present in the blood of about fifty people, living in both Spinetta Marengo and Alessandria. The investigation, aimed at looking for the presence of six particular PFAS, unfortunately yielded the expected results. In the blood of many of the residents who were tested, PFAS levels are high. Sometimes very high.

Riccardo Ferri, 56, sits on the fallen trunk of a 100-year-old tree in the garden of the Marengo Museum, where his parents met when they were young. In the background, less than a kilometer away, is the Solvay plant. Ferri joined a group of people from Spinetta Marengo who participated in the determination of various PFAS in blood performed by the University of Liege, in Belgium. Alessandria, Italy, January 19, 2023.

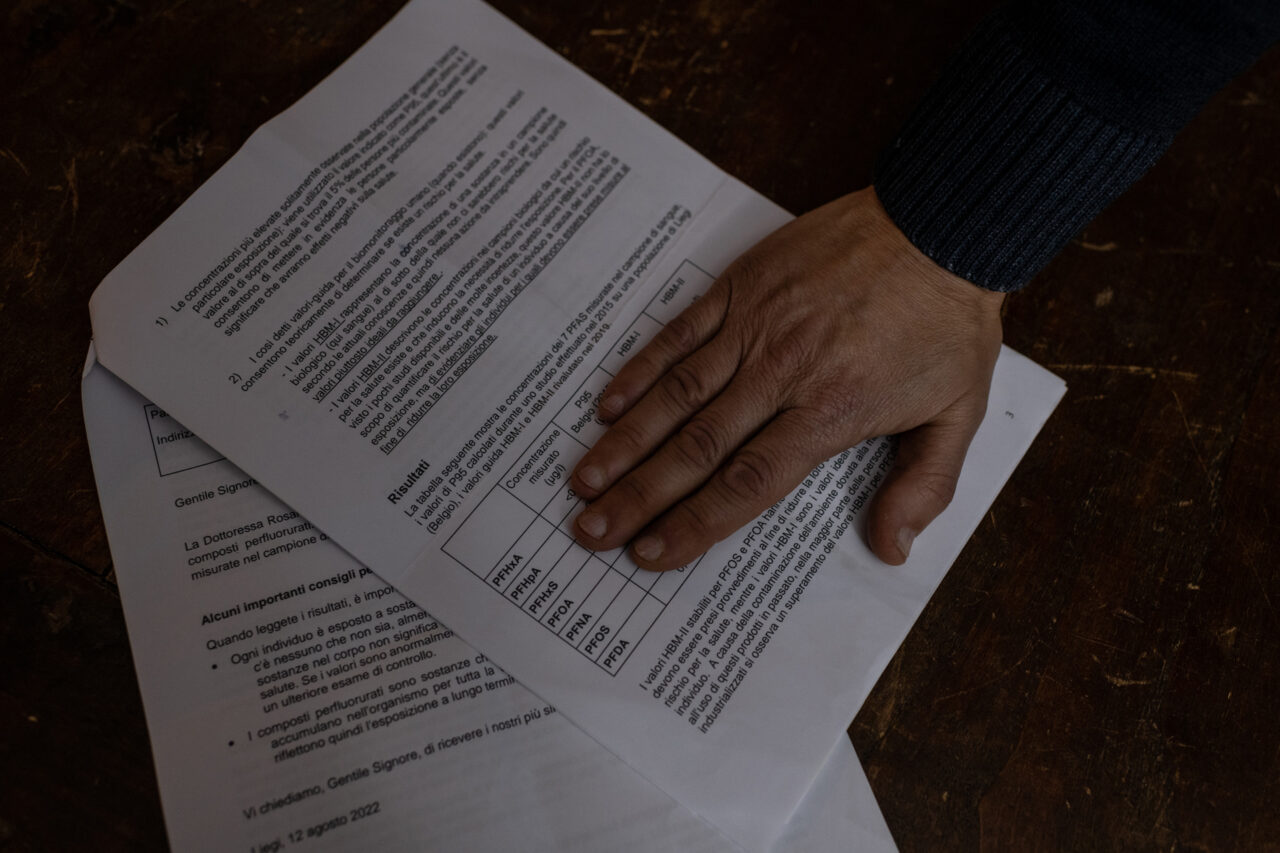

Riccardo Ferri, 56, covers with his hand the concentration of PFAS found in his blood. Ferri joined a group of people from Spinetta Marengo who participated in the determination of various PFAS in blood performed by the University of Liege, in Belgium. Alessandria, Italy, January 18, 2023.

«For years I thought that pollution from the chemical plant only affected the workers. I underwent the blood tests out of curiosity, after it was suggested to me by some friends of STOP Solvay», says Riccardo Ferri, a resident of Spinetta Marengo, «The samples were sent to the University Hospital of Liege, and after a few months a letter arrives at my home with the results. It showed that I had very high PFAS values, especially PFOA. It was at that point that I realized it was a problem. I went to my primary care physician, but he didn’t know what to say, much less what to do. There is no health protocol for these things.»

Riccardo Ferri, 56, stands in his car in front of the Solvay plant in Spinetta Marengo. Alessandria, Italy, January 19, 2023.

In 2022, a group of citizens from Alessandria and Fraschetta initiated and successfully concluded a signature collection to deliver a popular proposal for deliberation to the administration of the capital city. It calls, among many things, for institutions to establish as soon as possible a health protocol appropriate to the situation. The Creator and promoter of this initiative, Mirela Benazzo, has lived a painful story that has led her to commit herself wholeheartedly to demand the sanitary and environmental justice that had been lacking there for too long.

Never alone again

Mirella Benazzo’s dedication originated from events related to the illness that affected her father, who passed away in May 2021. Annamaria Leva, Mirella’s mother, recounts that «when they informed us that my husband was sick with lung cancer I was incredulous. He did not smoke. We lived a quiet life. they told me it could be environmental in origin; I couldn’t get it out of my mind. I, like many other people, also knew nothing about the pollution situation in Spinetta Marengo and Fraschetta.»

Mirella Benazzo and her mother Annamaria at their home in Castelceriolo. Mirella’s father died of lung cancer. Castelceriolo is a small village in Fraschetta near Spinetta Marengo. Benazzo submitted a civil petition to the municipality of Alessandria to request a biomonitoring of the population of the entire Fraschetta. Alessandria, Italy, January 21, 2023.

The odyssey that Mirella and Annamaria had to go through is very similar to that of so many other people who have seen loved ones fall ill and die: visits, second opinions, examinations, hopes and disillusionments. The need to make sense of what had happened can become a very powerful drive.

«I got in touch with Claudio Lombardi, I went to his house, he told me the whole story of the contamination of the places where we live and the epidemiological investigations. I was shocked», Mirella recalls, «some people told me that I was only committed out of a kind of stubbornness in wanting to understand the causes of my father’s death. This is not true. I do it because I don’t want other people to experience the situation that my mother and I experienced.»

Mirella and Annamaria attend some of the STOP Solvay committee meetings. These meetings take place online or at the Social Laboratory in Alessandria, a former fire station reclaimed, cleaned up and self-managed by dozens of local girls and boys. The reality of the Social Laboratory is not composed of a single collective, but of many voices. The people who are part of it struggle against the structural problems of the system in which we live and which they recognize in the city of Alessandria, provincial, regional and national institutions.

Read also: Everything you need to know about PFAS (in Italian)

Anita Giudice, 20, sitting on a bench at the Social Laboratory talks with Rosi Gatti, a retired family doctor who is also an activist with the civil organization STOP Solvay. The occupied fire station is a site potentially polluted by PFAS because of their use in foams to extinguish fires. Alessandria, Italy, December 14, 2022.

Understanding PFAS

«When we thought about what our battles would be, we could not exclude Solvay. The chemical plant is one of the first things you see when you arrive in Alessandria. It’s one of the things you remember most about the city», explains Anita Giudice, a part of STOP Solvay and the social laboratory, «but we also realized that we didn’t have the background to deal with it. Between the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, we met with the Mamme No PFAS [“No PFAS Moms”, the group of parents from the Veneto region that has been dealing with the very serious PFAS pollution situation in the provinces of Verona, Vincenza, and Padua for many years. Ed.] During an assembly they explained to us their story, the extent of the problem, and what it means to talk about PFAS. That’s how we started.»

Anita Giudice, 20, is an environmental activist who joined the civil organization STOP Solvay. The group meets at the Social Laboratory, an occupied space inside the old fire station in Alessandria. Alessandria, Italy, December 12, 2022.

The room at the Social Laboratory where the civil organization STOP Solvay keeps all materials for protest marches. Alessandria, Italy, December 14, 2022.

Dealing with PFAS is not easy. Knowledge on the subject is still in flux, and public science laboriously chases after research carried out by private companies. To understand this difficulty, one only has to consider the fact that even today it has not yet been established with certainty what is a PFAS and what is not. Definitions vary and with them the number of substances that can be considered PFAS changes. According to the most recent descriptions, there could be millions of PFAS. Public science knows the characteristics in detail of only a few dozen of these substances.

The right to speak

«Equipping ourselves to pursue our claims and not getting shot down is crucial. Sometimes, however, it seems that if you don’t have a high level of technical expertise you don’t even have the right to speak,» says Viola Cereda, a STOP Solvay activist who accompanied us through the streets of Spinetta Marengo near the perimeter of the factory. «Sometimes you can sense that arrogance of those who know the matter and belittle you. They don’t listen to you simply because you have fewer tools. But critical thinking can be exercised in different forms, and we know very well what Solvay’s faults are. These are indisputable facts.»

On October 15, 2022, there was the STOP Solvay Committee’s first public demonstration, with a procession that reached Alessandria’s City Hall. The demonstration was well attended and was also an opportunity to show the city a united and determined group of people. However – it should be remembered – the STOP Solvay Committee still represents a residual reality within the society of Alessandria. A large part of the population experiences the Solvay plant as something inescapable. Others, however, see it as a positive presence, capable of bringing jobs and well-being. Putting Solvay in a bad light, the latter argue, would only harm the community.

Yet the data on the presence of pollutants do not change. On the contrary, they get richer and richer. In this extremely complex context, institutions are struggling to give people an answer. The reasons, as we shall see, are many.

PART 2 – The institutions

Viola Cereda is an environmental activist who co-founded the organization STOP Solvay. Alessandria, Italy, January 21, 2023.

The following contributed to the publication of this article: Anna Violato, Alfonso Lucifredi, Marta Frigerio, Niccolle Ramirez Vilchez, Francesco Martinelli, Davide Michielin, Natalia Alana.

This investigation is a part of The Forever Pollution Project, a cross border survey in which 18 newsrooms from across Europe participated. A group in addition to RADAR Magazine includes Le Monde (France), Süddeutsche Zeitung, NDR and WDR (Germany), The Investigative Desk and NRC (The Netherlands) and Le Scienze (Italy), and also joined by Datadista (Spain), Knack (Belgium), Deník Referendum (Czechia), Politiken (Denmark), Yle (Finland), Reporters United (Greece), Latvijas Radio (Latvia), SRF Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (Switzerland), Watershed and The Guardian (United Kingdom).